The Aksumite Golden Age: Conquest Of Meroe & The Arrival Of Christianity

The century between 230 AD & 330 AD heralded the beginning of the Aksumite Empire's Golden Age. This period saw the minting of gold coins, expansion of economic, social & political power in the region

To View The Most Updated Version Of The Article Visit The Website:

What does Aksum mean? While the exact origin is unknown, some scholars believe it derives from the Agew word "Aku," meaning water, and the Semitic word "sum," meaning chief. Thus, it might refer to a "chief of water," possibly in reference to an ancient reservoir discovered by the region's early inhabitants, making it a suitable place for habitation. Interestingly, there is a place called Mai Shum (water chief) right next to Aksum in the present day.

Aksumite Empire Early 3rd Century AD

NGST ADBH & GRMT (~240AD)

Between the 220AD-240AD not much is known, this time period isn’t attested in any indigenous inscriptions but one can infer that due to the lack of Sabaic inscriptions during this period, that the Aksumite empire had held off from direct involvements with the south Arabian States, after the failed invasion by NGST BGYT of himyar, which was discussed in my previous article.

Following the defeat of the Aksumite forces in 220 AD at the capital of the Himyarite kingdom, Zafar, the next significant mention of the Aksumites in Sabaean inscriptions occurs around 240 AD. This period marks the reign of NGST ADBH, vocalized as Azeba or Adhebah, and his son GRMT, vocalized as Girma, Garima, or Garmat1. The geopolitical landscape during this era saw various rulers in northeastern Africa and Arabia.

Rulers in Northeastern Africa and Arabia

Aksumite Empire: NGST ADBH (Azeba or Adhebah)

Himyar: Shamir Yuhamid

Saba: Ilsharah Yahdub and Yazzil Bayyin

Expansion and Territories Under Aksumite Influence

During the reign of Emperor Azeba, the Aksumite Empire expanded its influence beyond its established territories in Arabia. Previously, under the reign of GDRT around 200 AD, the Aksumites had conquered the Kinaidokolpita and Arabitae tribes, located along the northern Arabian coastline across the Red Sea. However, under Azeba's rule, the Aksumites extended their control to new regions in southern Arabia, including As'aran, Ma'afir, Sawuma, and Saharatan. Of these, only Sawuma's location is precisely known, situated approximately 130 kilometers northwest of Aden. These regions were at the very least dependent on Aksum, if not direct colonies.2. During this time, the Aksumites formed an alliance with the Himyarites.

Theory: The Aksumites controlled new lands in southern Arabia through strategic alliances and treaties. An alliance between Himyar and the Aksumites likely followed an earlier peace treaty, which stipulated that several areas be placed under Aksumite jurisdiction. Sabaean inscriptions mention Aksumite wars with Himyar during the reign of Gadarat and his son Baygat. It is possible that another conflict occurred between the reigns of Emperor Baygat and Emperor Azeba, resulting in the acquisition of these territories.

Conflict Between Saba and Himyar-Aksum Alliance

A significant conflict erupted between the Sabaeans and the Himyar-Aksum alliance. The war started because of an accusation of a breach of an existing peace treaty by the Himyarites. The Aksumites, upon Himyar's request, aided Himyar3. This alliance led to Himyar consolidating more power in southern Arabia. The events of this conflict are detailed in Sabaean inscriptions JA 575 and 576, which provide a perspective of the Sabaeans on the war.

Sabaean Inscriptions

The inscriptions reveal that the Aksumites were defeated in the ensuing battles. Notably, Garmat, the son of Emperor Azeba, played a direct role in leading the Aksumite forces against the Sabaeans.

The inscriptions, particularly around line 26, also provide insights into the situation in Narjan. The Inhabitants had broken their alliance with the Sabaeans, and forged a new one with the Aksumites, in return the Aksumites offered them protection from Saba. Leading to a battle between the Aksumites and Sabaeans, in which the Sabaeans won.

19 From there they came back to the city Ṣnʿw in safety, in glory, with numerous spoils of battle, prisoners, booty, and prizes of war. After that Grmt, son of the Negus and with him armed bands of Abyssinians and of S¹hrtm committed hostilities against the kings of Sabaʾ, since S²mr ḏu-Raydān had asked them for help. And ʾlmqh granted them to inflict decisive defeat over them all. [... ...]

20 ḏu-Raydān. After that the king ʾls²rḥ Yḥḍb and with him some of his ʾqwl and one thousand soldiers from their army, and twenty six horsemen pursued them in order to take reprisals for the war waged and the assistance afforded to S²mr ḏu-Raydān at the time when there was a peace treaty between the kings of Sabaʿ and the Abyssinians.And they waged war against five settlements [... ...]

21 and they got from them numerous killings, prisoners, prizes of war, booty. And then some of Abyssinians and of S¹hrtm mounted an offensive against them and they caught the contingent of those Abyssinians on the hill of ʾḥdqm, and the fantry confronted against them. And ʾlmqh granted them to rout and destroy the contingent of those Abyssinians. And the king ʾls²rḥ Yḥḍb and his ʾqwl and his army

22 came back to the city Ṣnʿw in safety, in glory and with numerous spoils of war, prisoners, loot, and booty. And in praise because ʾlmqh granted them to defeat and take reprisals on Grmt, the son of Negus, the king of ʾks¹mn for (his ill-treatment of) the diplomatic delegation whom the kings of Sabaʾ had sent to him. And in praise because ʾlmqh granted them to defeat the officer Ṣḥbm, of the family [Gys²m ... ...]

23 from the dominions of ʾlmqh. And then they sent their mwtwy Nwfm, of the family Hmdn and Ġymn and with him some of their mqtyt and some of the two tribes of Ḥs²dm and Ġymn, and ʾlmqh granted them that their mqtwy Nwfm should come back in safety and also the appointed soldiers with him; and he defeated that officer Ṣbḥm, of the family Gys²m, and they brought back his head and his hands [... ...]

24 the tribe Ḫwln Gddm. And in praise because ʾlmqh granted the favour to subjugate the tribe of Ngrn when the latter had revolted and withdrawn the hand (the alliance) from their lords, the kings of Sabaʾ, in favour of Abyssinians. And the king ʾls²rḥ Yḥḍb and some of his ʾqwl, his army, and his cavalry waged war and they invested the city Ẓrbn for two months and they challenged [... ...]

25 they answered that they should inform their lords, the kings of Sabaʾ, that they were making the offense graver by having received a promise of protection by the king of Ḥaḍramawt against their lords, the kings of Sabaʾ and they promised to the tribe of Ngrn, for two months, to give protection against their lords, the kings of Sabaʾ. And the king ʾls²rḥ Yḥḍb and his ʾqwl, his army came back to the city [... ...]

26 and they heard that those of Ngrn had sent (ambassadors) to the armed bands of Abyssinians for helping the viceroy of the Negus in the city Ngrn and the tribe of Ngrn. They (the Sabaeans) had taken note of the promise given (by the Abyssinians) to those of Ngrn of protection against their lords, the kings of Sabaʾ, but made it unnecessary by their own committment to oversee the column of Abyssinians. After that, they sent two of their mqtwyy Nwfm, of the family Hmdn and of Ġymn and [... ...]

27 and they watched over them and some of the two tribes Ḥs²dm and Ġymn and fourteen of the cavalry, so they waged war to them in the two valleys of Ngrn. And they came back to their two lords, the two kings, in safety, in glory and with numerous killings, prisoners, and booty. After that the king ʾls²rḥ Yḥḍb gave battle to them [... ...]

28 they made raids upon them from their bases in the valley Rkbtn and all the principal men and freemen of the tribe Ngrn approached them with the offer of peace, in fact (the Sabaeans) killed among those of Ngrn scores of killing. In the third day, those of Ngrn tendered submission to their lord ʾls²rḥ Yḥḍb, king of Sabaʾand ḏu-Raydān; and as for the Abyssinian viceroy S¹bqlm [... ...]

29 those who had culpably initiated the revolt sent (ambassadors) to him, and they offered their sons and daughters as hostages, and they accepted into the city Ẓrbn the viceroy, whom his lord, the king ʾls²rḥ Yḥḍb ordered as viceroy in that city Ẓrbn and its valleys. The total of all those who had made submission from the city Ẓrbn and its valleys was [... ...] - Ja 576+Ja 577, South Arabian Inscription

Theory: Why did the Aksumites support Himyar against Saba? One theory suggests that the Aksumites saw Himyar, a relatively new state located at the southernmost tip of the Arabian Peninsula, as a strategic ally. The Aksumites controlled the northern Arabian Peninsula, with their territories bordering those of the Sabaeans, the dominant & established power at the time. Weakening and defeating the Sabaeans would have been crucial for the Aksumites to solidify their control in Arabia. Additionally, certain areas in Himyar were already dependent on or colonies of the Aksumites during this period, further proving this theory.

Aksumite Invasions Of Himyar ~250AD-270AD

Around 250 AD. An unnamed son of the Aksumite Emperor arrived at Zafar, the capital of the Himyarites, with his army. A battle ensued, but the Aksumites were promptly defeated. The Emperor who reigned during this invasion is unfortunately un-named but we can make a reasonable assumption it was Emperor Garmat.

Between 260 to 270AD, two Aksumite emperors named DTWNS (Vocalized Datawnas) and ZQRNS(Vocalized Zaqarnas) are mentioned as attempting invasions during the reign of Yasir Yuhan’im of Himyar4. Unfortunately not much is known about these two emperors, they might have been a father and son duo, as was the custom during this era.

Indigenous Inscriptions (240-260AD)

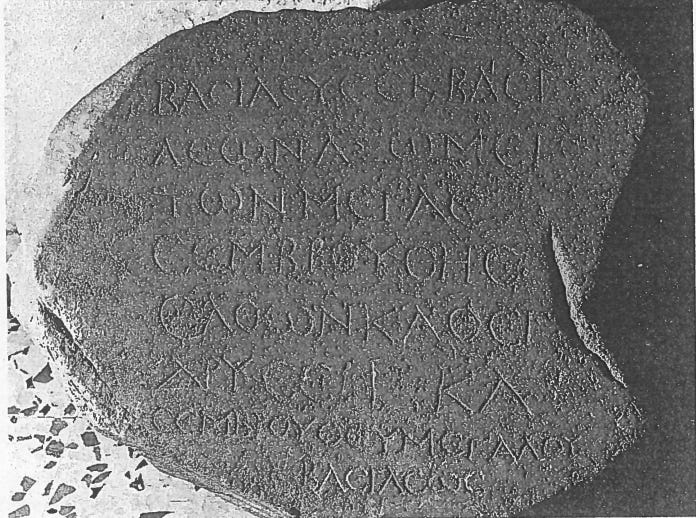

Emepror Sembrouthes

Between approximately 240 and 260 AD, there is a notable silence in the historical record regarding the names of Aksumite emperors

One significant inscription is attributed to an Aksumite emperor named Sembrouthes. This inscription was written on a stone tablet found in Dekemhare, present-day Eritrea. It is dedicated to the 24th year of his rule and is dated to around the 3rd century AD, which could fit this time period where a lack of other inscriptions detailing Aksumite rulers can be found5.

The inscription reads as follows:

"King of kings of Aksum, great Sembrouthes came (and) dedicated (this inscription) in the year 24 of Sembrouthes the Great King" - Aksum An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity, pg 74

Theory: King of Kings is a unique title not seen in other Aksumite Inscriptions, could this be in reference to a consolidation of power & a strict hiearchy being established during the 3rd century AD, therby allowing for the rise of the well known Aksumite emperors we will discuss later?

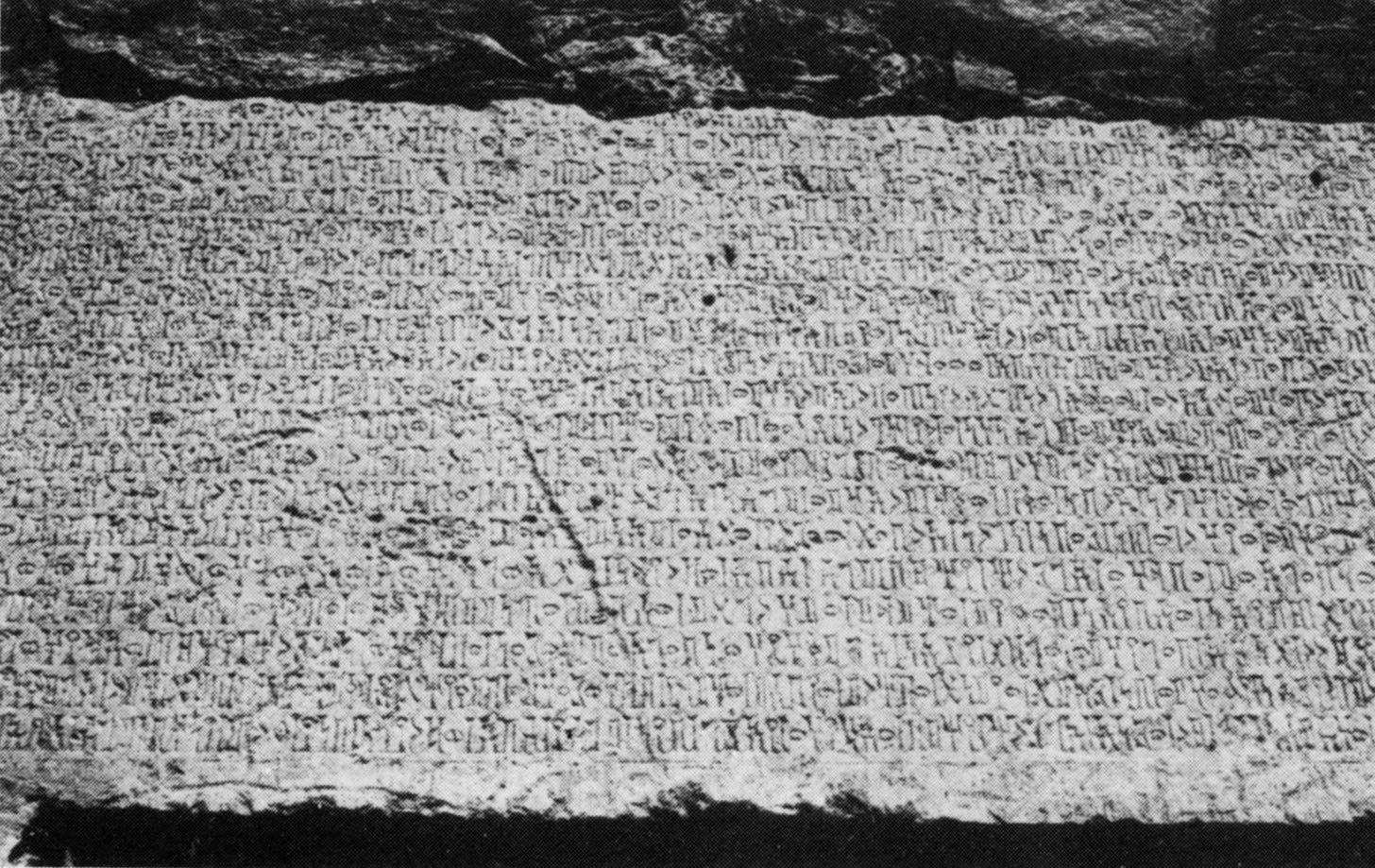

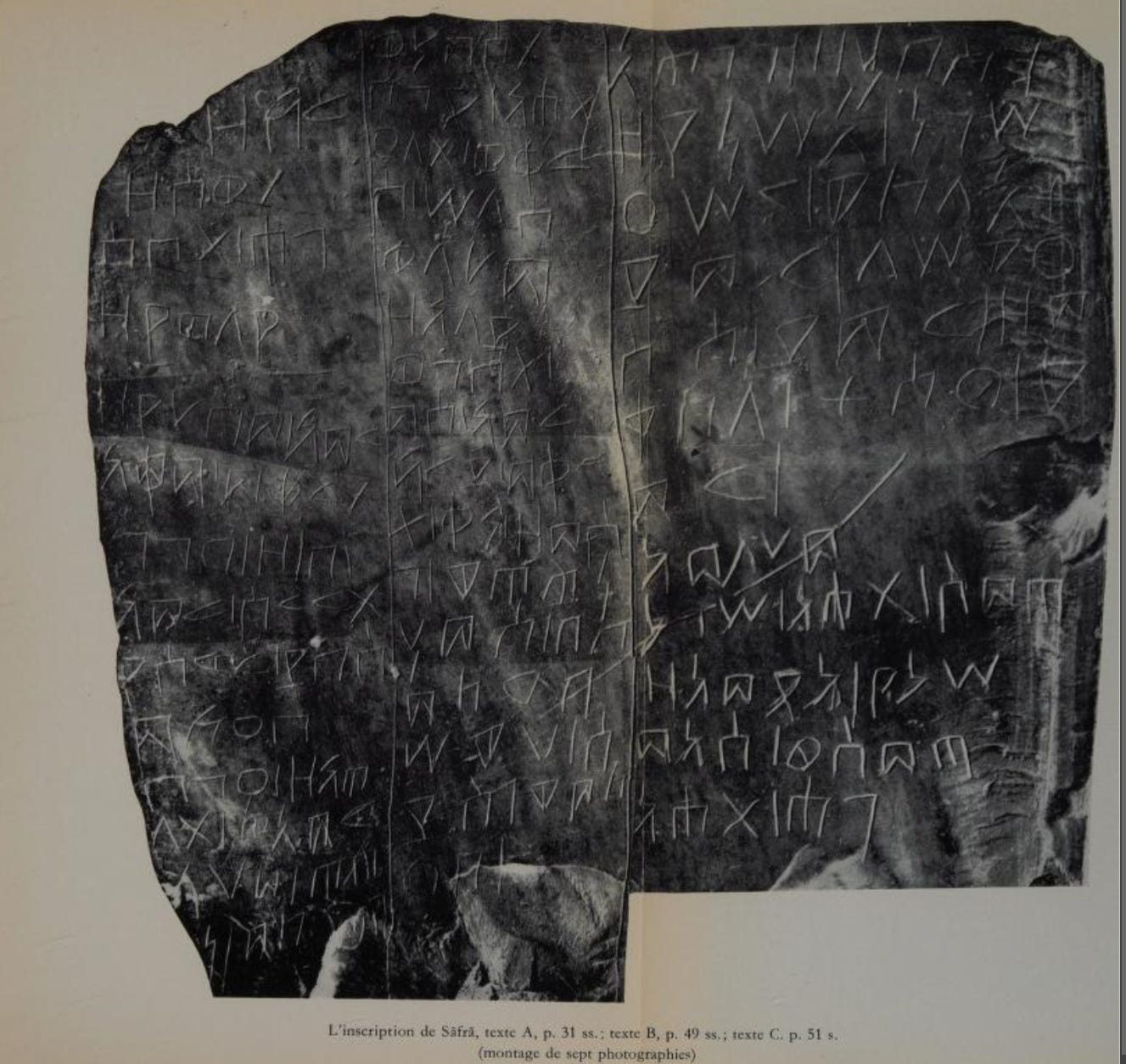

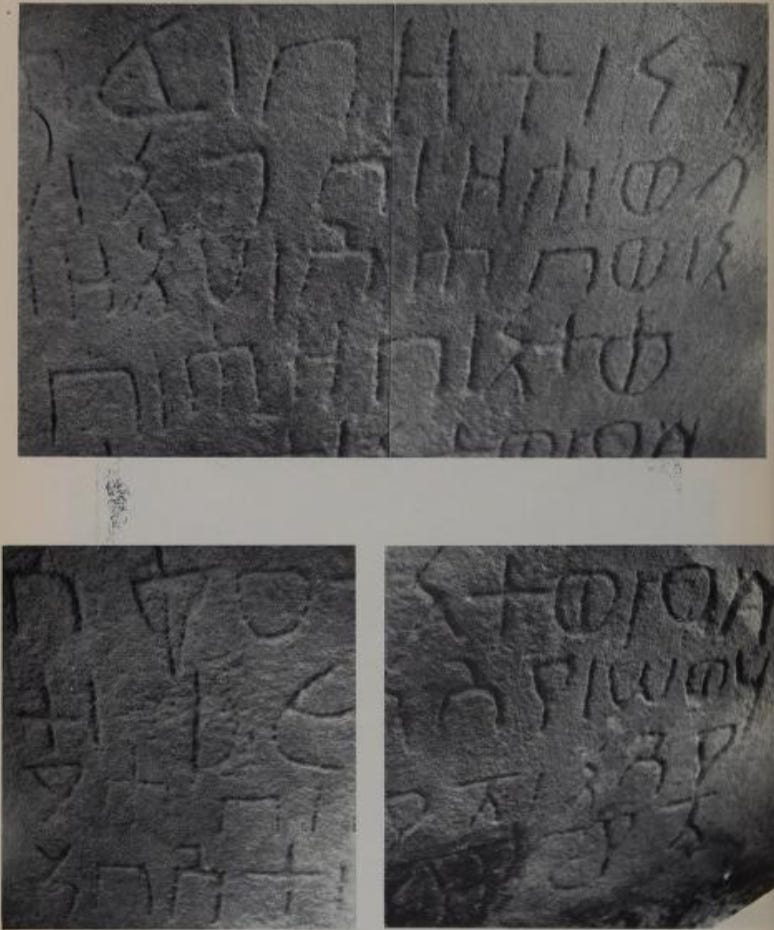

The Safra Inscriptions

The Safra Inscriptions, discovered in modern-day Eritrea at Zeban Kutur near Qohaito, are one of the oldest known Ge’ez inscriptions detailing laws. These inscriptions consist of four distinct texts arranged in columns, with three on the front and one on the back, carved into a stone slab measuring 24x24 cm and 1 cm thick6. Although each of the four texts contains different content, they are believed to date to the same time period. Text A (left side) lists laws, specifying that taxes were to be collected by the king and defining these taxes as consisting of both agricultural and pastoral products7. There is no mention of the author of the inscriptions.

The Anza Inscriptions, A Glimpse Into Aksumite Life

In Eastern Tigray, at a place called Anza, there is an inscription dating back to the 3rd century AD. This inscription details a certain king of Agabo who held a feast that lasted fifteen days, during which 520 jars of beer and 20,620 pieces of bread were given. The inscription is as follows:

"Has written Bizet King of Agabo [on] this stele of his own after he had subdued the people of Agabo he came in Qo’at in fifteen days and donated 520 jars of beer and bread he gave 20,620" - Ancient and medieval Ethiopian history to 1270, pg 89

Sembrouthes calls himself King Of Kings while Agabo calls himself just a king, therefore King Bizet was luckily a local ruler under the jurdistication of one of the Aksumite Emperors during this time. This inscription, while short does give us a glimpse into the festivites that took place within the empire at the time, we can only guess what this inscription was celeberating….it must have been something important for the king to order the creation of an inscription regarding it.

The Aksumite Golden Age

Emperor Endubis (~270AD-290AD)

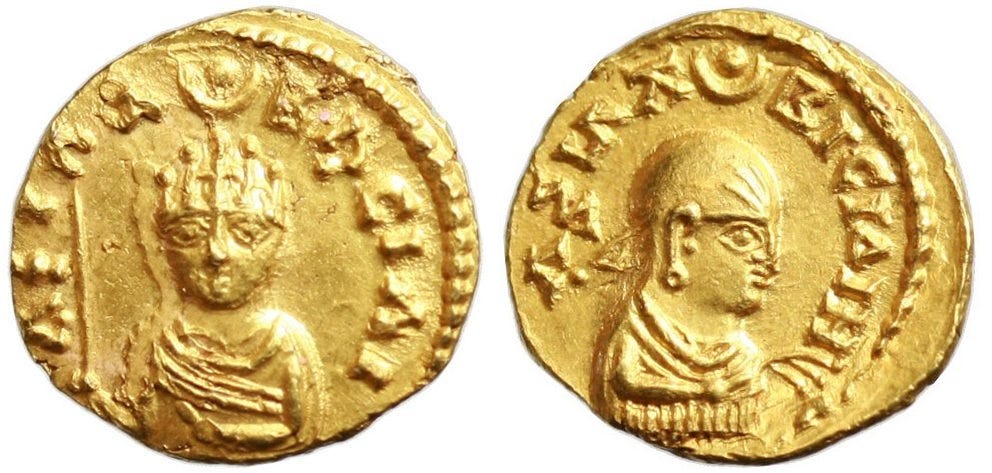

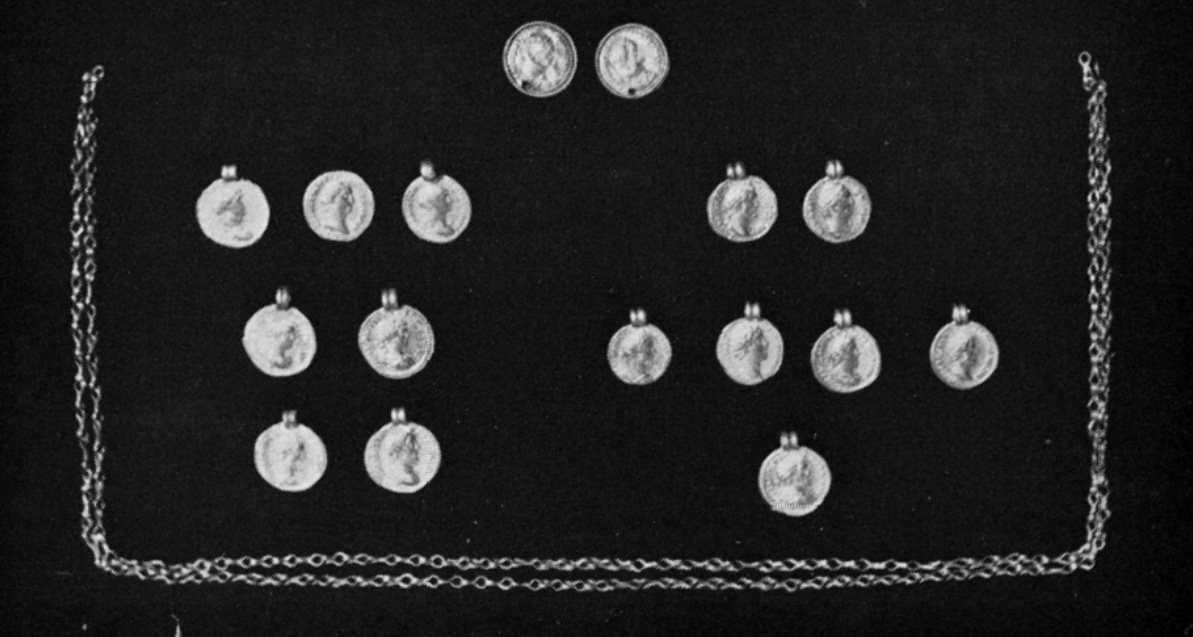

Around 270 AD, after the reigns of DTWNS and ZQRNS, Emperor Endubis ascended to the throne, marking a period of significant prosperity and development for the Aksumite Empire. This era saw the introduction of Aksumite coins, inspired by Roman coinage, these Aksumite coins featured Greek inscriptions on the outer edges reading "Basileus Aksomiton", meaning King of the Aksumites. Another title, "Bisi Dakhu," with Dakhu possibly referred to Endubi’s village or tribe named Dakhu. The coins depicted a side portrait of the king wearing a headcloth, with a sun and moon symbol above, which was a symbol of the pagan religion at the time, and ears of wheat or barley on either side. These coins were minted in Gold, Silver & Bronze.

The minting of coins hints at the centralization of the Aksumite political and economic structure during this period. Through these coins, the Aksumite Empire could project an image of strength and prosperity.

Emperor Aphilas (290AD-310AD)

After the reign of Emperor Endubis, coins from around 290 AD mention Emperor Aphilas. During Aphilas's reign, the Himyarite Kingdom, located to the east of the Aksumite Empire, conquered and annexed the Sabaeans8 . This expansion made the Himyarite Kingdom the dominant power on the Arabian side of the Red Sea. Around 300 AD, the Kinaidocpitae, a tribe along the northern Arabian coastline, rebelled against their Aksumite overlords and regained their independence with Roman support9. These developments resulted in the loss of most, if not all, of Aksum's remaining tributary states in Arabia10, diminishing the empire's influence in the region.

These turbulent events likely contributed to the brief reigns of Emperor Aphilas and his successor Wazeba. Aphilas, like his predecessor, minted gold, silver, and bronze coins featuring a side portrait of himself in the centre, flanked by two ears of wheat or barley. The outer edge bore a Greek inscription reading "Aphilas King," while the reverse side read "Bisi Dimele," with Dimele referring to his village or tribe11.

Notably, Aphilas's coins introduced two unique features: a front-facing portrait and the depiction of the emperor wearing a crown, marking a evolution in Aksumite coinage.

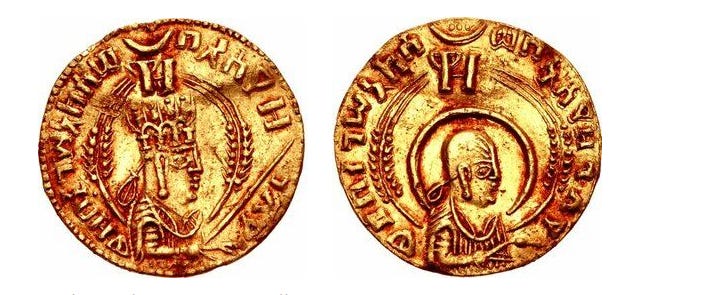

Emperor Wazeba

Coin reads: ወዘበነገሠአከሰመ በኢሰየዘገለየ/wazb ngus aksm besy zgly (unvocalized)

The next emperor depicted in Aksumite coinage is Wazeba. Information about Wazeba is limited due to the scarcity of his coins, likely a result of his short reign. Interestingly, Wazeba was the first Aksumite emperor to mint coins with Ge’ez inscriptions instead of Greek12. This shift suggests an increased focus on domestic trade, which makes sense given the loss of territory in the Arabian Peninsula during his predecessor Aphilas's reign. To recover revenue losses, it was essential to boost trade within their African territories.

Some of Wazeba's coins depict both him and his successor Ousanas13, suggesting that Ousanas might have acted as a regent during the latter part of Wazeba's reign. This dual depiction indicates possible political turmoil and further supports the notion of Wazeba's brief rule.

The Great Stele Of Emperor Aphilas/ Wazeba

In Aksum, there is a subterranean royal burial ground, directly above on the surface there are multiple stelaes, three of which are of immense size. Stele 3 stands 20.6 meters tall and weighs approximately 160 tonnes14. This stele, representing a ten-story building, possibly symbolized a structure for the emperor in the afterlife.

Unlike the other two large stelae, Stele 3 has never collapsed at any point. None of the three major stelae bear any Christian inscriptions, indicating they likely commemorate different pre-Christian Aksumite emperors. Scholar D. W. Phillipson theorizes that Stele 3 was erected during the reign of Emperor Aphilas or Wazeba15.

Emperor Ousanas & The Arrival of Christianity (~320AD-330AD)

Emperor Ousanas, known indigenously as Ella Amida, ruled after Wazeba. Scholars believe that during Ousanas' reign, two Tyrian boys from Tyre (located in southern Lebanon and controlled by the Eastern Roman Empire at the time) were captured and brought to the emperor's court16. The younger boy, Aedesius, became the cupbearer, while the older boy, Frumentius, became a tutor to the emperor's son.

There are two main accounts of how these two boys ended up at the emperor's court. One major account comes from Rufinus, a Roman historian who is said to have translated the story directly from Aedesius. Another account is found in "The Synaxarium of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church," which details the lives of saints in the Ethiopian Orthodox Church and also mentions Frumentius and Aedesius17. I will now discuss each account separately.

Arrival Of Christianity - Rufinus

The following excerpt from Rufinus, a 4th Century roman philosopher & historian describes the arrival of Christianity in the Aksumite Empire:

One Metrodorus, a philosopher, is said to have penetrated to further India in order to view places and see the world. Inspired by his example, one Meropius, a philosopher of Tyre, wished to visit India with a similar object, taking with him two small boys who were related to him and whom he was educating in humane studies. The younger of these was called Aedesius, the other Frumentius. When, having seen and taken note of what his soul fed upon, the philosopher had begun to return, the ship on which he travelled put in for water or some other necessary at a certain port. It is the custom of the barbarians of these parts that, if ever the neighbouring tribes report that their treaty with the Romans is broken, all Romans found among them should be massacred. The philosopher's ship was boarded; all with himself were put to the sword. The boys were found studying under a tree and preparing their lessons, and, preserved by the mercy of the barbarians, were taken to the king. He made one of them, Aedesius, his cupbearer. Frumentius, whom he had perceived to be sagacious and prudent, he made his treasurer and secretary. Thereafter they were held in great honour and affection by the king. The king died, leaving his wife with an infant son as heir of the bereaved kingdom. He gave the young men liberty to do what they pleased but the queen besought them with tears, since she had no more faithful subjects in the whole kingdom, to share with her the cares of governing the kingdom until her son should grow up, especially Frumentius, whose ability was equal to guiding the kingdom—for the other, though loyal and honest of heart, was simple. While they lived there and Frumentius held the reins of government in his hands, God stirred up his heart and he began to search out with care those of the Roman merchants who were Christians and to give them great influence and to urge them to establish in various places conventicles to which they might resort for prayer in the Roman manner. He himself, moreover, did the same and so encouraged the others, attracting them with his favour and his benefits, providing them with whatever was needed, supplying sites for buildings and other necessaries, and in every way promoting the growth of the seed of Christianity in the country. When the prince for whom they exercised the regency had grown up, they completed and faithfully delivered over their trust, and, though the queen and her son sought greatly to detain them and begged them to remain, returned to the Roman Empire. Aedesius hastened to Tyre to revisit his parents and relatives. Frumentius went to Alexandria, saying that it was not right to hide the work of God. He laid the whole affair before the bishop and urged him to look for some worthy man to send as bishop over the many Christians already congregated and the churches built on barbarian soil. Then Athanasius (for he had recently assumed the episcopate) having carefully weighed and considered Frumentius’ words and deeds, declared in a council of the priests: ‘What other man shall we find in whom the Spirit of God is as in thee, who can accomplish these things?’ And he consecrated him and bade him return in the grace of God whence he had come. And when he had arrived in India as bishop, such grace is said to have been given to him by God that apostolic miracles were wrought by him and a countless number of barbarians were converted by him to the faith. From which time Christian peoples and churches have been created in the parts of India, and the priesthood has begun. These facts I know not from vulgar report but from the mouth of Aedesius himself, who had been Frumentius’ companion and was later made a priest in Tyre. - Ancient and medieval Ethiopian history to 1270, pg 99 - 100

The Journey of Metrodorus and His Students to the Aksumite Empire

Rufinus recounts the story of Metrodorus, a philosopher from Tyre, who embarked on a journey to the Aksumite Empire. Metrodorus' expedition was driven by exploration, curiosity, and philosophical inquiries, similar to the pursuits of his ancient predecessors. Accompanying him were two young boys under his tutelage, Aedesius and Frumentius. Aedesius was the younger of the two, while Frumentius was the older brother. Their journey took them across the Red Sea, eventually reaching Aksumite territory.

Encounter with Barbarian Raiders

Upon docking at a port within Aksumite territory, Rufinus notes an intriguing aspect of the geopolitical landscape of the time. He mentions that barbarian tribes were permitted to raid Roman ships, loot, and kill Romans aboard if a neighbouring tribe had broken its treaty with the Romans. This "neighbouring tribe" likely referred to the Aksumites, who controlled extensive territories on the African side of the Red Sea. The Aksumites exerted direct control over the coastline through various ports, the largest being Gabaza at Adulis, as documented in the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea.

Despite their control, it was impractical for the Aksumites to monitor the entire coastline continuously, and peripheral tribes inhabited significant portions of it.

As mentioned previously, around 290-300 AD during the reigns of Ousanas' predecessors, Wazeba and Aphilas. The territory in the north, bordering Roman Arabia, had revolted with Roman support, leading to political consequences and the cessation of trade treaties between the Romans and the Aksumites.

The Attack and Capture

Rufinus describes how the cessation of treaties allowed peripheral tribes to loot and pillage Roman ships found crossing the Red Sea without permission. It was under these conditions that Frumentius and Aedesius travelled. While the boys were studying under a tree—indicating that their ship was docked, possibly for resupply or rest—barbarians seized the opportunity to attack. The barbarians killed and looted the ship's crew, including Metrodorus. However, they spared the two boys, possibly seeing their potential value.

The boys were taken to the Aksumite Emperor, and the barbarians likely received a reward once the boys' value was revealed. Aedesius, due to his younger age, was assigned the ceremonial role of a cupbearer. Frumentius, being older and more knowledgeable, was given the role of treasurer and secretary. This role was likely bestowed after he had spent some years acclimatizing to the land, culture, and language, and proving his loyalty to the emperor. Frumentius' knowledge and skills impressed the emperor, securing his high position.

Frumentius Becomes a Bishop

Upon the death of Emperor Ousanas, his son Ezana ascended to the throne. During this transitional period, the queen sought to retain loyal advisors to support the young king. Frumentius and Aedesius, having established a special connection with the royal family, were seen as trustworthy and thus the queen promised they could leave once the young princes had grown up. The queen played a significant role in royal duties, supported by court officials, while King Ezana was still young. Acting as a regent until Ezana and his brother Sazena grew older.

Rufinus notes that Frumentius helped ease tensions with the Romans, allowing Roman merchants to build places of worship and practice Christianity throughout the Aksumite empire. When Ezana reached adulthood, the regency ended. Fulfilling the queen's promise to the brothers, Aedesius returned to Tyre to reunite with his parents, while Frumentius traveled to Alexandria to seek ordination from the patriarch Athanasius. Frumentius was consecrated as a bishop and returned to the Aksumite Empire to continue his work.

Arrival Of Christianity - The Synaxarium of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church

The Synaxarium of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church is an Indigenous recount of the various saints of the church, the following excerpt recounts the story of Frumentius and Adesius.

And on this day also died Abbā SALAMA, the Revealer of the Light, the Bishop of Ethiopia; now his history is as follows: A certain man from the country of the Greeks, a master of learning whose name was MERPES (MEROPIUS?) came wishing to see the country of Ethiopia, and he had with him two youths of his family, and the name of one was "FERE MENATOS (FRUMENTIUS)", and that of the other was "ADESYOS (AEDESIUS)"; now there are some who call him "SIDRAKOS"; And he arrived in a ship at the shore of the sea of Ethiopia, and he saw all the beautiful things which his heart desired, and as he was wishing to return to his country, enemies rose up against him and killed him, and all those who were with him. And these two youths were left [alive], and the men of the city made them captives, and taught them the work of war, and took them as a present to the king of 'AKSUM' whose name was "ALAMEDA". And the king made ADYOS (sic) director of his household, and FERE MENATOS keeper of the laws and archives of 'AKSUM'; and after a few days the king died, and left a little son with his mother, and the 'AZGAGA reigned with him. And 'ADESYOS and FEREMENATOS brought up the children, and taught them little by little the Faith of Christ, and they built for them a place of prayer, and they gathered together to it the children and they taught them psalms and hymns. And when they had brought the boy to the stage of early manhood, they asked him to dismiss them to their native country; and 'Adyōsēs (sic) departed to the country of Tyre to see his kinsfolk, and FEREMENATOS departed to Alexandria, to the Archbishop ATHANASIUS, and he found that he had been restored to his office, And he related everything which had happened unto him because of their Faith in the country of Ethiopia, and how the people believed on Christ, but had neither bishops nor priests. And then Abbā ATHANASIUS appointed FEREMENATOS Bishop of the country of Ethiopia, and sent him away with great honour: And he arrived in the country of Ethiopia during the reign of 'ABREHA. - A Translation of the Ethiopic Synaxarium, XXVI - HAMLE p1162

The traditional account of Frumentius and Aksum offers a detailed glimpse into the historical and cultural context of the period. This account is enriched with names and roles of key figures, providing a deeper understanding of what had occurred.

Key Figures and Rulers

During this period, the emperor ruling Aksum was Alameda, also known as Ella Amida (Ousanos). He was the father of Ezana, who later played a pivotal role in the Christianization of the Aksumite Empire. Frumentius and Aedesius, two important historical figures, served as tutors to the emperor's children, including Ezana. They were instrumental in teaching Christianity to the young princes, thereby planting the seeds of a major religious transformation.

Frumentius and His Mission

After being ordained in Alexandria as a bishop, Frumentius returned to Aksum during the dual kingship of Abreha and Asbeha. Abreha and Asbeha were the titles used by Ezana and his brother Sazena, respectively. Frumentius' mission was to spread Christianity throughout the Aksumite Empire, a task he undertook with dedication and success.

Indigenous Name and Legacy

Frumentius is also known by his indigenous Ge'ez name, Abba Salama, which means "Father of Peace." This name reflects his significant role in spreading Christianity across the Aksumite Empire, promoting a doctrine that contrasted with the previously dominant pagan beliefs. The Aksumite pagan religion was polytheistic, worshipping multiple gods, one of whom was Mahrem, the god of war.

Transformation of Aksumite Society

The introduction of Christianity brought profound changes to Aksumite society. Previously, the society, particularly the core of which wasHabesha, was more militaristic and inclined towards violence, a characteristic embodied in their worship of Mahrem. Christianity introduced doctrines of peace and passivity, which significantly influenced the cultural and social dynamics of the region.

Ousanas’s Invasion Of The Kushite Empire

Aksumite-Kushite War During the Reign of Ousanos

Historical Context

During the reign of Emperor Ousanos, the Aksumite Empire declared war on the Kingdom of Kush. The Kingdom of Kush had been a dominant power in the region for centuries, but by the 3rd century AD, its influence was waning due to various political and socio-economic issues. These internal problems weakened the Kushites, making them more vulnerable to external threats. On the other hand, the Aksumites were actively seeking to expand their influence within Africa after losing territory in the Arabian Peninsula. This combination of Kushite decline and Aksumite ambition created a context ripe for conflict between the two powers.

Evidence of Conflict

An inscription found in Meroe, the capital of the Kingdom of Kush, details the conquests of a king of the Aksumites and Homerites. Scholars believe this inscription was left after the conquest by Emperor Ousanos18. Initially, some scholars attributed the downfall of the Meroitic Empire to Emperor Ezana, Ousanos's son. However, further analysis has led most scholars to conclude that it was indeed Ousanos who conducted the war against Kush.

Notably, when Emperor Ezana later conducted his own invasion to crush a rebellion in Kushite territory, he did not mention any Meroitic kings. This absence suggests that by the time of Ezana's campaign, the Meroitic kings no longer existed, indicating that the territory had already been conquered during Ousanos's reign. The lack of mention of Meroitic rulers in Ezana's records supports the conclusion that Ousanos was the one who brought down the Meroitic Empire19.

The inscriptions found at Meroe reads as follows:

(The King?) of the Axumites and Homerites

...(before) Ares they contented...

...having heard him, from the ... (I departed)

...and I devastated the (upper lands?) ...

...(I) having passed by (the sanctuary that is) closed.

...it is produced, and another ...

...along with the king as far as the ...

...(the ) holy things (or places) to the king in the...

...goats and children

...I passed them (by) ...

...houses ...

...earring ...

...copper (or bronze)

...and... - Ancient and medieval Ethiopian history to 1270, pg 91

Aksumite Empire Trade (3rd Century AD)

Relations with Rome

During the 3rd century AD, the Aksumite Empire, ruled by GDRT and his sons, bordered the Romans on both sides of the Red Sea. Although direct relations between the two empires during this era are not well-documented due to a lack of inscriptions, the presence of Roman coins from the 2nd and 3rd centuries at Aksumite sites like Matara suggests some form of interaction20.

Trade with India

In-land trade with India wasn’t always reliable for the Romans and had considerable taxes levied because of rival intermediary states such as Sassanids in Persia, which were located in-between India and other eastern powers & Rome in the west. Thus trade routes through the Red Sea were sometimes favoured, most of the trade with Indian civilizations was done by proxy through people inhabiting the Red Sea such as merchants living in Adulis. During this time, the regions of Ethiopia and India were interchanged quite frequently especially when talking about the region near Aksum. In addition to this gold coins from India dating to the 3rd century AD have been found In Debre Damo21.

Conclusion

The beginning of the Aksumite Golden Age heralded significant developments, including the minting of coins, the vocalization of the Ge'ez script, the building of monumental stelae, the arrival of Christianity, and the successful invasion of the ancient Kushite Empire. These advancements culminated in the reign of one of Aksum's most renowned emperors, Emperor Ezana. Despite facing numerous rebellions throughout his empire, he erected many great inscriptions detailing his triumphs and constructed numerous tombs. Most importantly, during Ezana's reign, the Aksumite Empire officially transitioned to Christianity, marking the beginning of over 1600 years of Christianity in the region. Christianity would play a significant role in the nation's history. The next article will discuss the rebellions during Emperor Ezana's reign, the Nine Saints, and much more. Thank you for reading, and I hope you enjoyed it.

Sources & biblography

In terms of sources, I used a wide range of them. I primarily used primary sources, however, I also read the following books:

Aksum An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity

The Throne of Adulis: Red Sea Wars on the Eve of Islam

Foundations of an African Civilisation AKSUM & THE NORTHERN HORN 1000 BC-AD 1300

Aksum An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity, pg 73

Ancient and medieval Ethiopian history to 1270, pg 79

Aksum An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity, pg 73

Aksum An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity, pg 74

Aksum An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity, pg 73

Foundations of an African Civilisation AKSUM & THE NORTHERN HORN 1000 BC – AD 1300, pg 64

Aksum An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity, pg 81

Aksum An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity, pg 77

Ancient and medieval Ethiopian history to 1270, pg 80

Aksum An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity, pg 77

Ancient and medieval Ethiopian history to 1270, pg 82

Aksum An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity, pg 76

Aksum An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity, pg 76

Foundations of an African Civilisation AKSUM & THE NORTHERN HORN 1000 BC – AD 1300, pg 142

Foundations of an African Civilisation AKSUM & THE NORTHERN HORN 1000 BC – AD 1300, pg 145

Aksum An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity, pg 77

Ancient and medieval Ethiopian history to 1270, pg 98 & 99

Ancient and medieval Ethiopian history to 1270, pg 92

Ancient and medieval Ethiopian history to 1270, pg 92

Ancient and medieval Ethiopian history to 1270, pg 79

Ancient and medieval Ethiopian history to 1270, pg 85