ደብረ ዳሞ/Dabra Dammo

A 1,500-Year-Old Aksumite Monastery, On-Top Of A Natural Fortress That Withstood The Test of Time.

Introduction

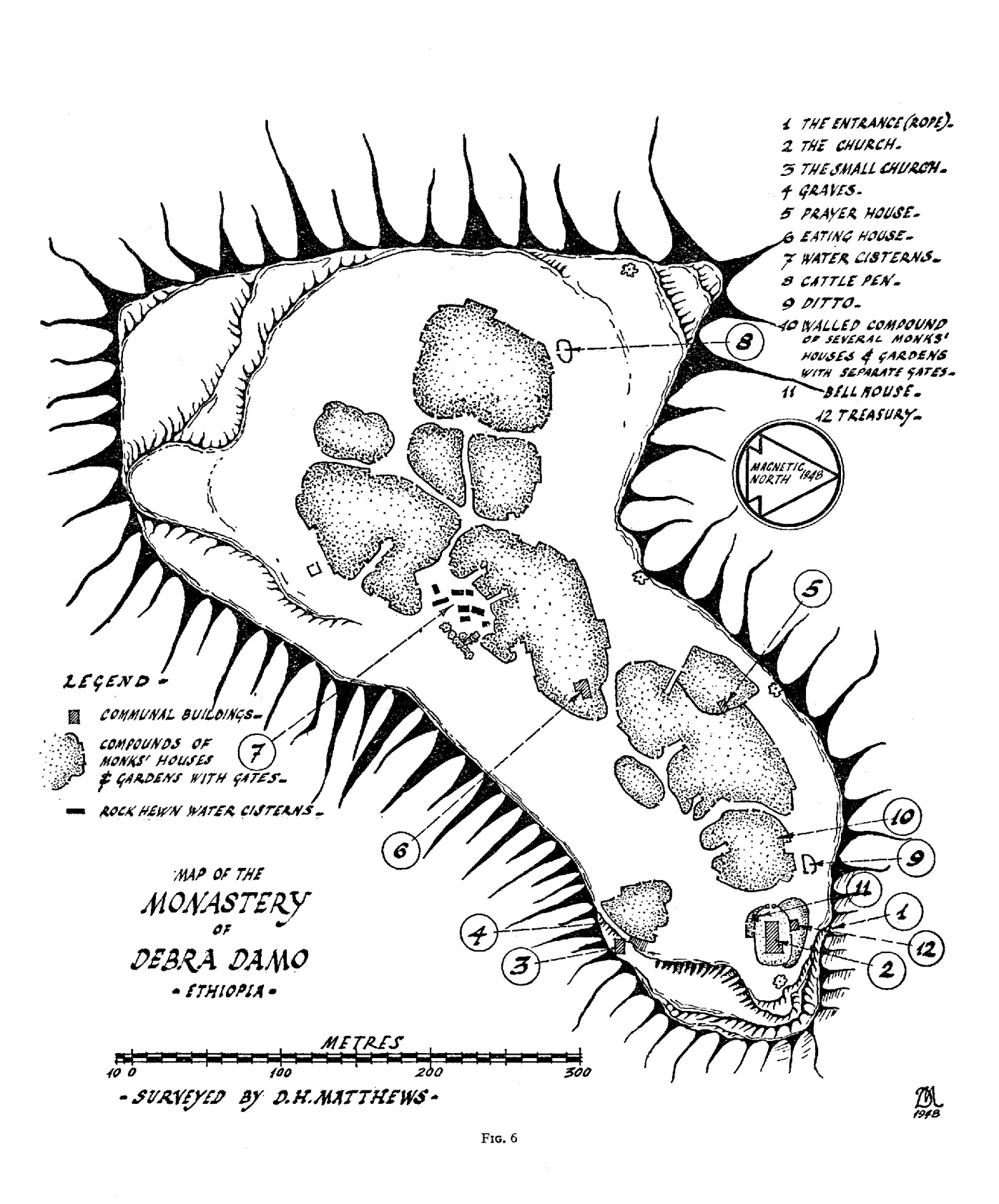

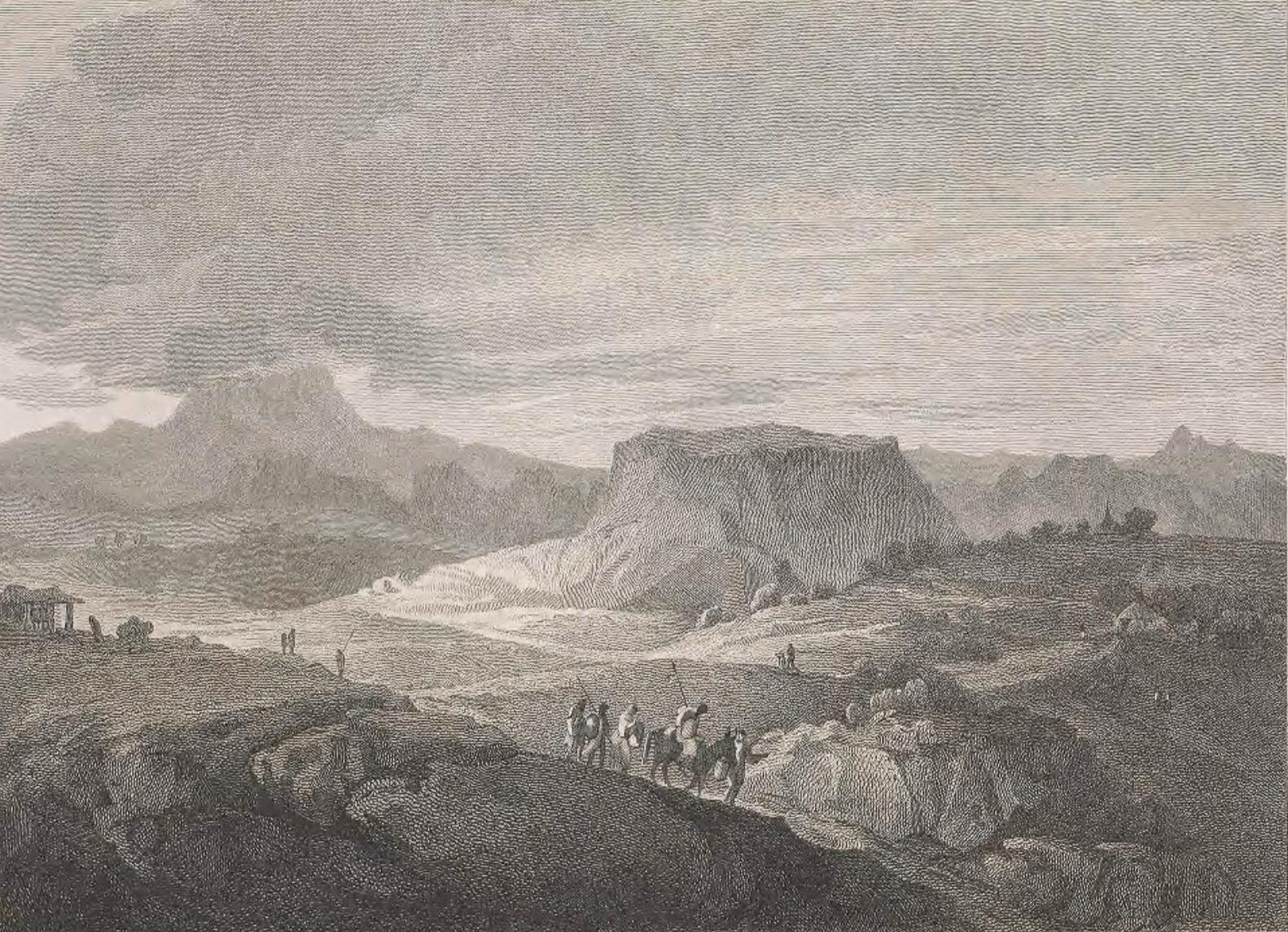

Dabra Dammo, located at the northern edge of the province of Tigray in modern-day Ethiopia and about 20km north-west of the city of Adigrat, rests atop a distinctively flat-topped mountain (known as an Amba - እምባ in Tigrinya). The mountain spans approximately 600 meters from northeast to southwest, with an average width of 180 meters, resembling a fortress with sheer cliffs dropping over 50 meters on all sides. Rising to an altitude of 2,215 meters above sea level, its natural defences were so formidable that in the 16th century1, Empress Seble Wongel took refuge atop the mountain and even after a year-long siege, Ahmed Gragn’s large army was unable to capture it.

"Dabra Dammo" is the accurate English transliteration of the Tigrinya term "ደብረ ዳሞ”. Occasionally, the Amharic variant "Dabra Damo" is also used.2

Dabra Dammo is currently open only to men, with even female animals prohibited. The exact timing of this rule’s enforcement is unclear, currently, women visit the church of Kidane Mehret (Covenant Of Mercy) church, located near Dabra Dammo instead.

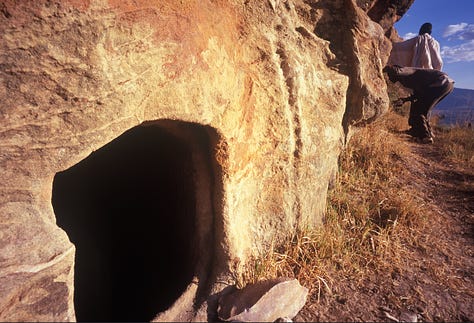

Access to the mountain is via the northeastern side, where visitors scale the cliff using a 17-meter leather rope. An additional rope is tied around the waist, allowing a monk to assist by pulling the person up during the ascent. Then the visitor enters the gatehouse and makes their way up a pathway to the top of the mountain.

Atop Dabra Dammo, two churches stand on the far northeastern side. The first is the notable main church, while the second, a smaller one lies near the cliff edge to the south of the main church, both are dedicated to Saint Aregawi. This smaller church is built over several caves that act as grave sites, one of which legend claims belongs to Saint Aregawi himself3. Scattered across the mountain-top are clusters of stone houses where over 100 monks reside, along with gardens and groups of cisterns at the centre of the Amba used to collect rainwater.

History

Origin

According to the Gadla Aregawi (which translates roughly to "The life story of Aregawi"), Abune Aregawi was born in the 5th century AD in the Roman Empire to a noble family. His father, Yeshaq, was a Roman prince, and his mother, Edna, was a princess4. He was named Michael at birth, and from a young age, he embraced the monastic life. Under the guidance of Father Pachomius, he became an exceptional teacher of the Gospel in the Roman Empire and earned the title "The Elder," or Aregawi in Tigrinya.

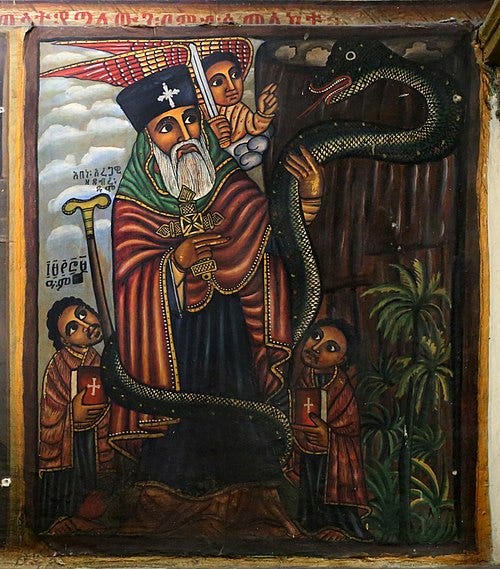

Along with several other saints, now collectively known as the Nine Saints, Aregawi journeyed to the Aksumite Empire during the reign of Emperor Kaleb's father, Ousanas II. Upon arrival, Aregawi was welcomed by the Emperor, who granted him permission to preach in his kingdom. Guided by the Holy Spirit, Aregawi ventured to a steep mountain that seemed impossible to climb. However, through divine intervention, the Archangel Michael appeared and commanded a massive serpent, over 60 meters long, to assist him in scaling the mountain. Once he reached the summit, Aregawi praised God, saying, "Hallelujah to God the Father, Hallelujah to God the Son, Hallelujah to God the Holy Spirit”. The mountain was thereafter named Dabra Haleluyah5.

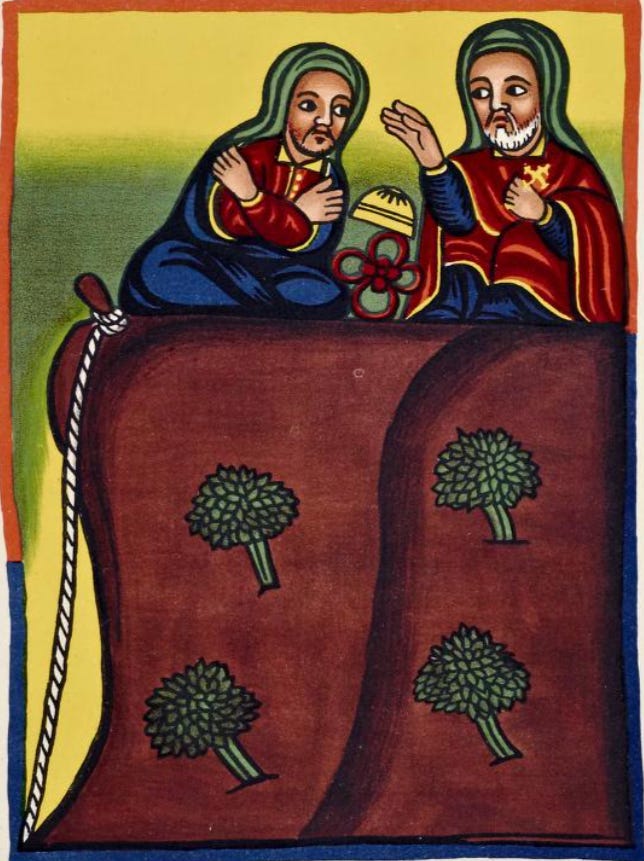

Soon, the site became a place of pilgrimage, attracting worshippers. To facilitate access, a large stairway was constructed. However, Aregawi was displeased with this development and asked Emperor Gebre Meskal to "Dahmimo"—to destroy it. He prophesied that no stairs, ladders, or paths should be built on the mountain as a lasting reminder of the miracle that allowed him to reach the top. Instead, a rope was used to ascend the mountain, this would also allow every visitor to experience a similar feeling of joy Aregawi felt when he reached the top. Thus the name of the mountain became Dabra Dahmimo, later evolving to the current form, Dabra Dammo6.

“The building of the church of Debra Damo. Gabra Maskal sent his army to collect materials and workmen with knowledge; he sent to the north, east, south, and west and they brought carts, ladders, and equipment. The carts were three and a half metres long for the stone. He made a ramp in order that the animals and workmen could climb. They brought water and stone from below. He built the church with a lot of wood, fashioned into a good shape. It is very good and takes your heart. He finished the building in two years and built it after he had been king for one year. He collected all the necessary furnishings for the church, and gave them to the monastery. He gave twelve gold crosses, and gospels in gold and silver, and the story of Paul, and everything else that is necessary for a church.” - Excerpt from Gadla Abuna Aragawi from The Monastery of Debra Damo, Ethiopia By DEREK MATTHEWS, pg 28

When Saint Aregawi reached the top, he is said to have dropped his cross. The stone which it dropped on is kissed by visitors when entering the church.

Aksumite Era

Dabra Dammo continued to function as a monastery after the deaths of Saint Aregawi and Emperor Gebre Meskal. However, according to local tradition, as confirmed by monks at Debre Dammo, it also served as a royal prison for Aksumite princes, preventing rivals to the throne7. This practice was similar to the use of Amba Gishen during the Solomonic era and Amba Wähni during the Gondarine period.

This tradition was shared with explorer James Bruce in the 18th century and later with Derek Matthews, who, during his exploration of Dabre Dammo in 1959, was told the same story.

Later, during the fall of the Aksumite Empire around the 9th-10th century AD, Queen Gudit is said to have built a ramp and led her forces into Dabra Dammo, her forces then looted, destroyed and massacred the inhabitants8. A priest at Dabre Dammo also mentioned to Derek Matthews that one of the large cisterns was excavated around the time of Empress Gudit’s Pagan occupation.

Archeologists have discovered a large number of foreign coins of Arab origins dated to the 8th to 10th century AD, right around the time of Empress Gudit, this might be yet another hint of foreign occupation during this era9.

Solomonic Era

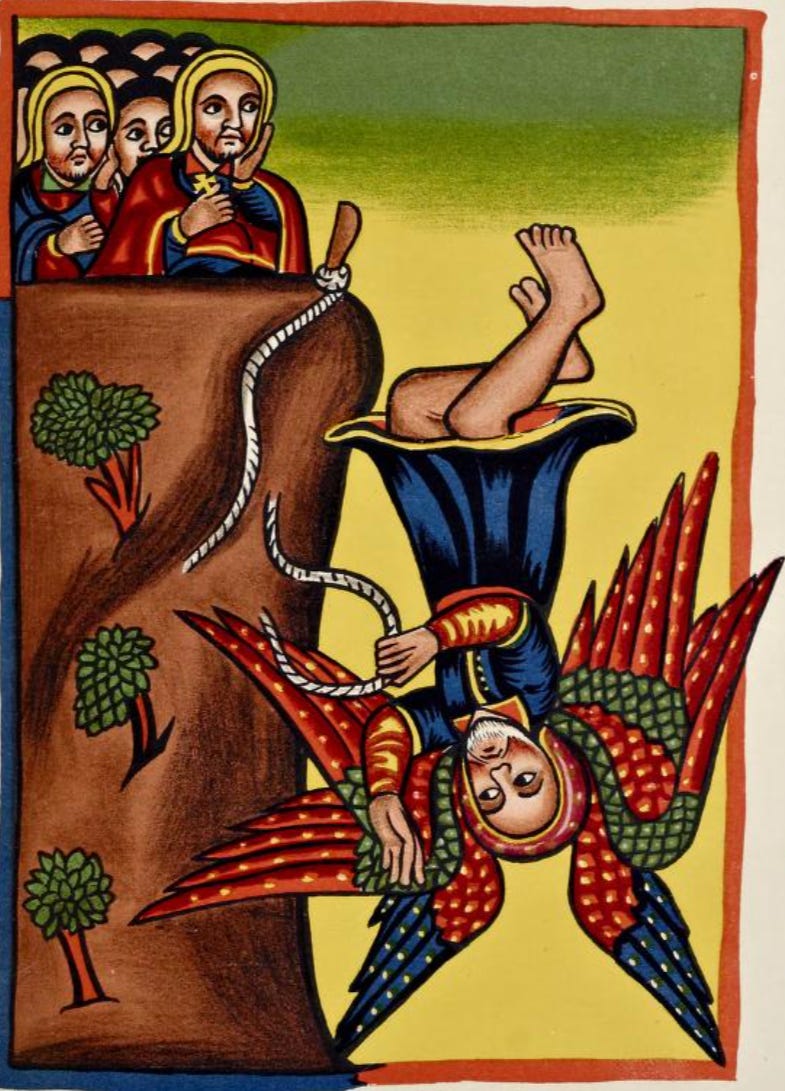

At the beginning of the Solomonic era (or more precisely just prior to it) around the early 13th century AD, Saint Takla Haymanot is said to have studied at Dabra Dammo as a monk for twelve years. When he was ready to leave, Abba Yohanni held onto the rope while Takla Haymanot descended. However, as he descended, the rope snapped immediately, causing him to fall. At that moment, a miracle occurred: six wings appeared, breaking his fall, and he rose into the air, flying away.

Later, during the early Solomonic era, Dabra Dammo became an important centre of ecclesiastical doctrine with numerous Emperors such as Amda Seyon I giving donations to the church10 as well as Baeda Maryam I11.

The next significant event in its history occurred during the invasion of Abyssinia by Ahmad Gragn in the early 16th century. At this time, Ahmad Gragn, ruler of Adal had controlled most of Abyssinia, but Dabra Dammo remained one of the few safe havens in Tigray. Miguel de Castanhoso recounts how Cristóvão da Gama travelled to meet Empress Sabla Wangel, who had sought refuge there with her entourage for several years. During this period, Ahmad Gragn unsuccessfully attempted to capture the site for over a year, with Emperor Lebna Dengal dying and being buried at Dabra Dammo in 1540.

"That at one day's journey away was the Queen, Mother of the Preste, in a very strong mountain, to which she had retreated with her women and servants on the death of her husband, then Preste, and that D. Christovao should send for her, as her presence was necessary by reason of the country people, that they hould bring supplies of food, and necessaries. When he heard this, and learnt how near the Queen was, he was very joyful, and at once sent to inform her that he had arrived with the Portuguese for the service of herself and her son, and that he would send one hundred soldiers to return as her guard, as it was very necessary that Her Highness hould personally live among her people ; because in this way she would be better obeyed and we better received. started at once, and arrived the same day late at the foot of the hill, where they pitched their tents, and notified to the guard of the hill that the Portuguese had arrived to be the [Queen's] guard and attendants ; she was greatly pleased, and with much content ordered the guards to allow the two captains to ascend the hill. When they arrived at the entry to the hill, there were lowered to themv ery strong thongs of leather, to which was attached a contrivance like a large basket, and they were told that the Queen ordered them both to ascend, as she wished to see them while she was getting ready to start.

They obeyed, each ascending by himself in the basket ; they were taken to the Queen's lodgings, who received them very hospitably, and talked much with them, asking them ofthe coming of D. ChristovSo, and of the Portuguese he rchildren, for so she called us. She got ready immediately, with all her women and servants, leaving on the mountain started at once, and arrived the same day late at the foot of the hill, where they pitched their tents, and notified to the guard of the hill that the Portuguese had arrived to be the [Queen's] guard and attendants ; she was greatly pleased, and with much content ordered the guards to allow the two captains to ascend the hill. When they arrived at the entry to the hill, there were lowered to them very strong thongs of leather, to which was attached a contrivance like a large basket,^ and they were told that the Queen ordered them both to ascend, as she wished to see them while she was getting ready to start. They obeyed, each ascending by himself in the basket ; they were taken to the Queen's lodgings, who received them very hospitably, and talked much with them, asking them of the coming of D. ChristovSo, and of the Portuguese her children, for so she called us. She got ready immediately, with all her women and servants, leaving on the mountain

When the morning came, the Queen, whose name was Sabele Oengel,' with all her ladies and her women, got ready for the march, and the Portuguese with her ; and because this mountain is the strongest there is in the country, and the most precipitous that ever was seen, I will explain here the manner of its fortification, for it appears constructed by the hands of God to preserve this lady and her following from captivity, and to prevent the destruction of the monastery of friars on the summit, in which the service of God is constantly performed. For the King of Zeila came against it with all his power for a year, but could never capture it ; and this not out of desire for the treasures that were in it, for there were none there and he knew it well, but to get the Queen into his hands, whom he much desired, as she is very beautiful.

When at the end of the year he found that he could not capture it by starvation, he struck his camp and marched away, for he discovered the manner of the fortification, which is in this wise. The summit is a quarter of a long league in circumference, and on the area on the top there are two large cisterns, in which much water is collected in the winter ; so much that it suffices and is more than enough for all those who live above, that is, about five hundred persons.' Onthis summit itself they sow supplies of wheat, barley, millet, and other vegetables.' They take up goats and fowls ; and there are many hives, for there is much space for them ; thus this hill cannot be taken by hunger or thirst. Below the summit the hill is of this kind. It is squared and scarped for a height double that of the highest tower in Portugal, and it gets more and more precipitous near the top, until at the end it makes an umbrella all round, which looks artificial, and spreads out so far that it overhangs all the foot of the mountain, so that no one at the foot can hide himself from those above ; for all round there is no fold or corner, and

there is no way up save the one narrow path, like a badly-made winding tair (caracol), by which with difficulty one person can ascend as far as a point whence he can get no further, for there the path ends. Above this is a gate where the guards are, and this gate is ten or twelve fathoms above the point where the path stops, and no one can ascend or descend the hill save by the basket I have above mentioned. Thus this hill cannot be captured if even only ten men guard it ; as for the fortress, it is the custom of the country that the princes who are not the first in succession are at birth taken to this hill, and remain there and are brought up as king's sons, but never leave it or see any other country ; unless the heir who accompanies his father dies, when they take the eldest from the hill ; the others remain until the heir marries, and has sons, and sits on the throne, which he cannot do save on his father's death.

Therefore, when the heir has sons, the princes leave the hill and go to their lordships, which have been already defined for them. These precautions are taken because the people are so evil that, on any dispute with the heir, if one of the princes were at large they would rebel under him ; thus this custom I describe has arisen because they meet with so little loyalty among them. - The Portuguese expedition to Abyssinia in 1541-1543 as narrated by Castanhoso, pg 12 - 17

From the passage above, we can infer that Dabra Dammo was extremely self-sufficient, with a natural water source captured through its cisterns and a variety of food produced from its gardens, including wheat, barley, lentils, goats, and chickens. Additionally, as all sides of the mountain were steep, the only entry to the site was through the gatehouse, which could only be accessed via a rope pulley system. This system allowed people to be pulled up in a large basket, making the site highly defensible and difficult to invade.

Given these natural defences, it is not surprising that Ahmad Gragn eventually abandoned his attempt to capture Dabra Dammo. However, this raises the question: Why didn't Gragn build a large ramp, similar to the one constructed by Queen Gudit during her rebellion?

If we are to trust the above account, instead of Emperors, local princes were exiled at Dabra Dammo during the Solomonic period.

In 1557/58, during the Ottoman invasion of Abyssinia led by Özdemir Pasha, the Ottomans captured the port of Massawa, marking the beginning of a deeper incursion into the region. This led to the occupation of Medri Bahri's capital, Debarwa, and their forces pushed even further, reaching as far as Debre Dammo. At Debre Dammo, the Ottoman troops are reported to have captured and massacred the monks dwelling there. They also desecrated the graves of Emperor Lebna Dengal and Saint Aregawi, in addition to causing destruction to the church itself. However, the site was eventually recaptured by Emperor Gelawdewos.

“In the nineteenth year of his reign, while he was saddened for the devastation of monasteries and villages at the hands of the soldiers of Özdemir (Uzdǝmer), who were Turks, and while he was even more languid because the Turks went up to the top of Däbrä Dammo and they killed the righteous and pious who were inside it, and defiled the blessed land by the walk of their impure feet and fast to shed blood and for their entering into the sacred place sanctified by the presence of holy relics inside it and by its carrying of the pure body of the right King Lǝbnä Dǝngǝl and by the fact that Abba Arägawi, tribe of pious and righteous men, peace be upon them, were buried there: in his sadness, he appealed to God glorious and most high, saying: ‘Lord, the heathen entered into your inheritance and they defiled your holy temple. They have converted the church into ruins like the hut of yield keeper; they have made of the dead body of your servants food for the birds of the sky and also of the flesh of your righteous for the beasts of the wilderness; they have shed their blood like water around the church and there was no one to bury them” - CHRONICLE OF KING GÄLAWDEWOS (1540–1559) Translated By Solomon Gebreyes, pg 46 & 47

Following this period, Debre Dammo became a point of interest for various foreign explorers, including Manoel Barradas, James Bruce, Henry Salt, and Samuel Gobat and documented as part of the Deutsche Aksum-Expedition in the early 20th century AD12.

Modern-Day

The Main Church - Enda Abba Argawi

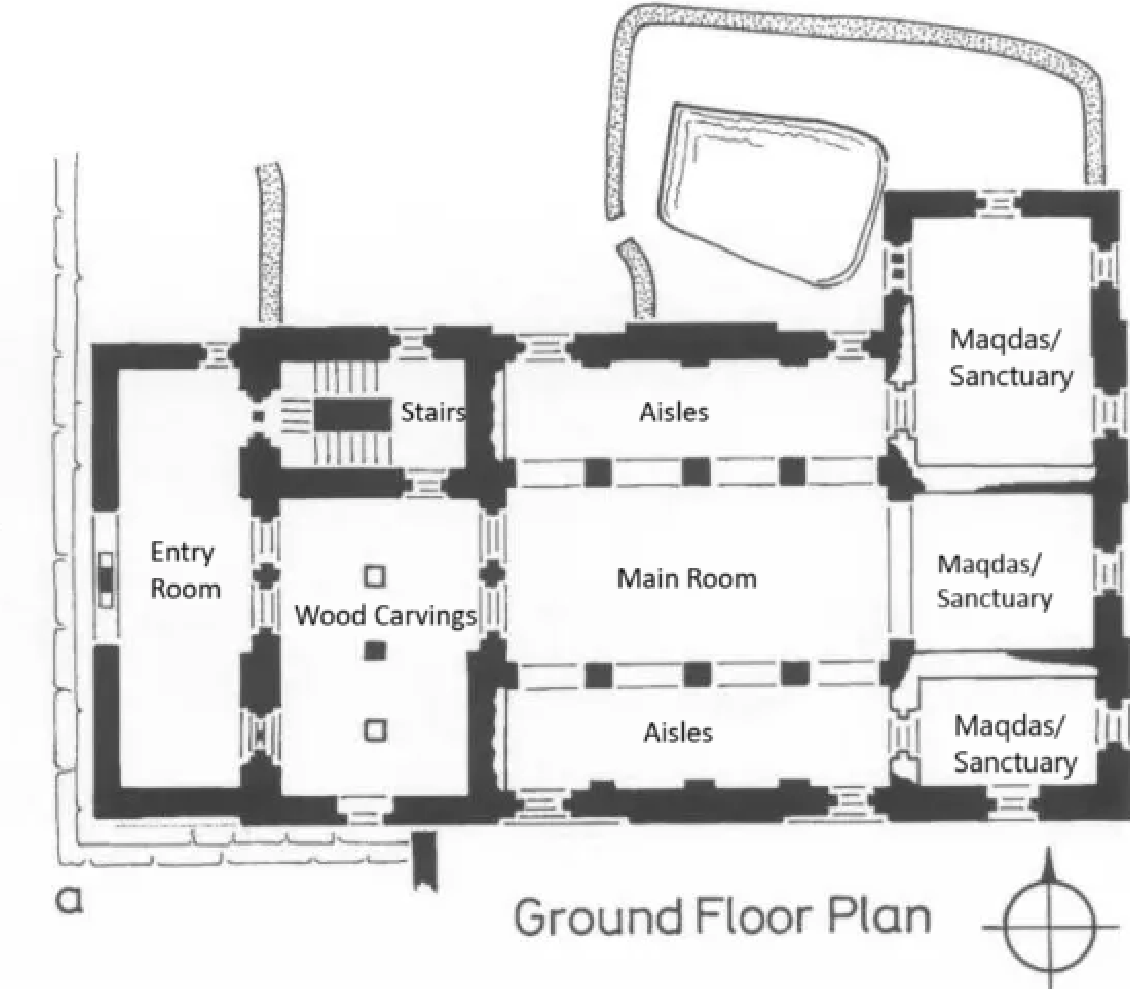

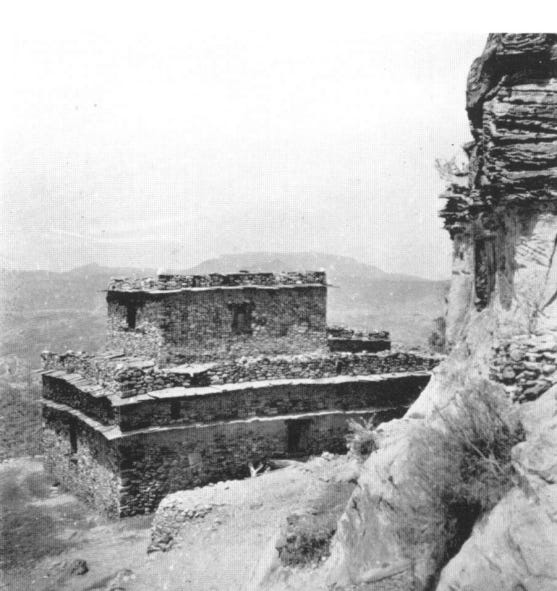

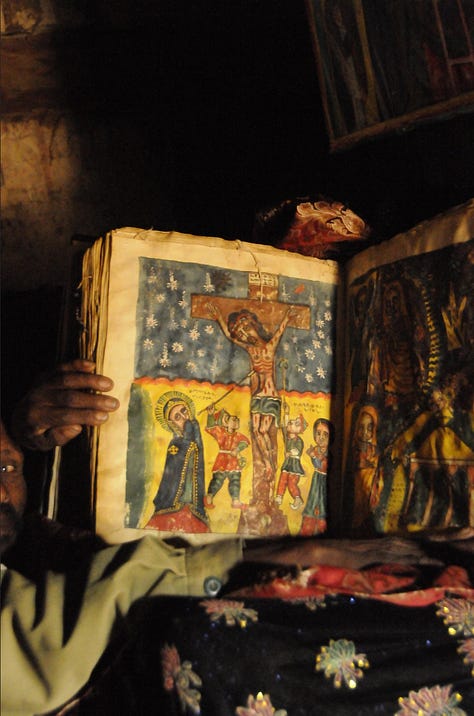

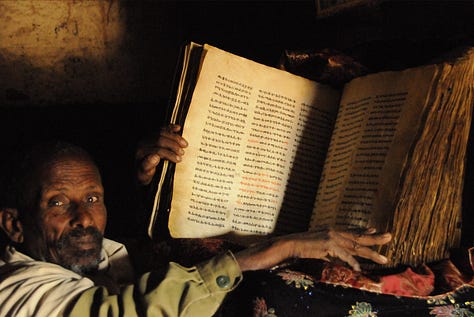

The main church at Dabra Dammo is located on the northeastern corner of the mountain, and alongside it is a bell tower and treasury, which is used to house many ancient manuscripts. The main church is a two-story, rectangular structure measuring 19.8m in length and 9.6-12.3 metres in width (depending on the place), and 10m in height13. The walls of the main church are constructed in the Aksumite style, featuring vertical and horizontal timber beams (with the ends projecting out - called a “monkey head” and is a common characteristic of Aksumite architecture) filled with stone and earth mortar. The main entrance is a stone-pillared double doorway on the western side.

The church was likely originally 17.1 by 9.6m, with later extensions being added to the western and northeastern sections14. The earliest sections of the church likely date back to the sixth or seventh century AD15.

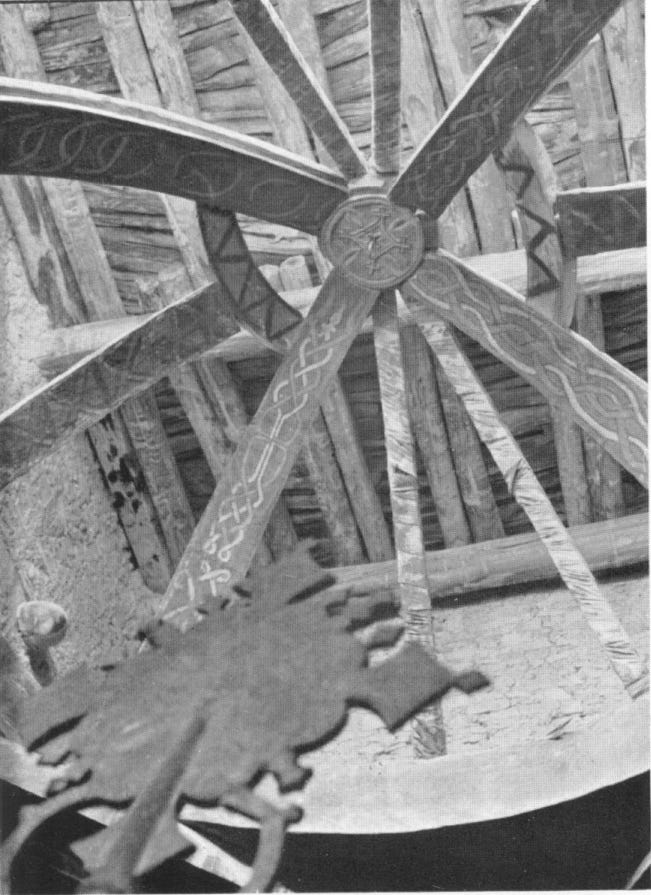

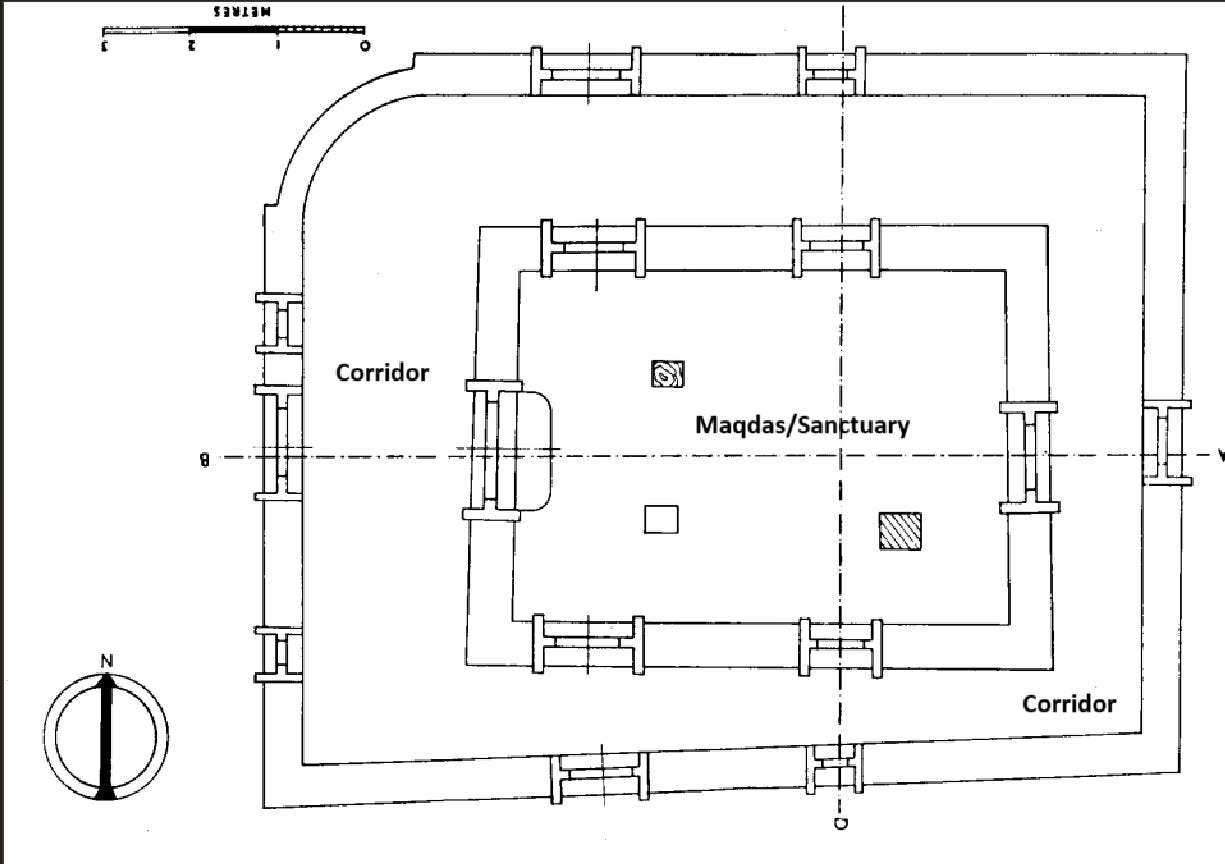

The primary western entrance opens into an anteroom(entry room), which features a double doorway on its eastern side leading to a pillar-supported room. This room is supported by three pillars—one of stone and two of wood—and boasts an intricately carved wooden ceiling adorned with various animal motifs, including camels, cattle, snakes, and antelopes. Toward the north of this room, a doorway leads to a smaller chamber with a staircase ascending to the second floor. An eastern double doorway from the pillar-supported room provides access to the main part of the church, which is divided by six pillars into the nave (central section) and two side aisles. This area, known as the Qeddest/Kiddest, this is where Holy Communion is received. Each side aisle also includes a doorway that opens to the exterior16.

The easternmost part of the church is known as the Maqdas (Room of Sanctuary), and only the priests are allowed in. The ceiling is constructed of timber and includes a 2m diameter dome, it is said that the coffin of Emperor Lebna Dengel is also housed in the northern section of this room17.

The Smaller Church

To the south of the main church lies a ledge, overlooking a smaller church 20 metres below, venerated as the site where Saint Aragawi is believed to have disappeared. Rectangular in shape and standing 6.2 metres tall, this church has an entrance on the western side and is constructed from large, roughly cut stones joined by mud mortar, without the timber interlacing seen in the main church. The roof is accessible via an external staircase. Inside, there is a corridor that spans the whole building, three additional doors lead to the inner maqdas (sanctuary)18. To the right of the altar in this area, there is an opening in the floor that descends to an underground cave, approximately 1.7 metres below, where Saint Aragawi is said to have vanished. Archaeologists estimate that this smaller church was built after the larger one, likely post-15th century, and also suggest that an earlier structure previously existed here predating the current.

Caves & Burial Sites

Alongside this smaller church, along the same ledge, are numerous ancient caves now used as burial sites for the monks of Dabra Dammo. According to local tradition, Saint Takla Haymanot once resided in one of these caves during his time at Dabra Dammo, and it is said that Saint Aragawi occasionally appears in one of these caves. Remarkably, coins from the Umayyad Caliph Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan, dated to 697 AD and 703 AD, were discovered in one of the caves. Archaeologists and historians suggest these coins may have been offerings from visiting pilgrims after battles with Muslims. Additionally, a horde of 1st-3rd century coins from the Kushan Empire (Modern-day Pakistan & Northwestern India) were also found near this location, alluding to the possibility that the mountain had been occupied prior to Christianity19.

It’s possible that Dabra Dammo was home to an important pagan site, for the worship of the god Arwe (traditional serpent god), not only is this motif found in the origin story of Saint Aregawi & Dabra Dammo but wooden carvings of serpents are also present in one of the rooms at the main church, therefore it’s not a stretch of the imagination to believe this theory.

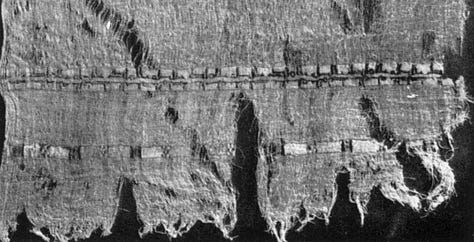

Fragments of foreign cloth, primarily silk from Coptic sources, dating from the sixth to eighth centuries, have been uncovered in these caves. These cloths were traditionally used to wrap relics and sacred objects. Additionally, cloths from the Tulunid and Fatimid periods of Egypt, dating from the ninth to twelfth centuries, were also found. Carvings of crosses also adorn the cave walls.

Interestingly it’s usually foreign coins that have been found thus far in Dabra Dammo with the only known example of an Aksumite coin being of Emperor Armah.

Ancient Churches of Ethiopia, by David W. Phillipson, pg 51 & 52

Ancient Churches of Ethiopia, by David W. Phillipson, pg 55

Ethiopia, the unknown land : a cultural and historical guide, pg 336

Matthews, D., & Mordini, A. (1959). I.—The Monastery of Debra Damo, Ethiopia. Archaeologia, pg 29

Matthews, D., & Mordini, A. (1959). I.—The Monastery of Debra Damo, Ethiopia. Archaeologia, pg 29

Matthews, D., & Mordini, A. (1959). I.—The Monastery of Debra Damo, Ethiopia. Archaeologia, pg 54

Matthews, D., & Mordini, A. (1959). I.—The Monastery of Debra Damo, Ethiopia. Archaeologia, pg 34

Matthews, D., & Mordini, A. (1959). I.—The Monastery of Debra Damo, Ethiopia. Archaeologia, pg 56

Matthews, D., & Mordini, A. (1959). I.—The Monastery of Debra Damo, Ethiopia. Archaeologia, pg 57

Ancient Churches of Ethiopia, by David W. Phillipson, pg 55

Ancient Churches of Ethiopia, by David W. Phillipson, pg 62

Ancient Churches of Ethiopia, by David W. Phillipson, pg 64

Ancient Churches of Ethiopia, by David W. Phillipson, pg 57-60

Ancient Churches of Ethiopia, by David W. Phillipson, pg 62

Matthews, D., & Mordini, A. (1959). I.—The Monastery of Debra Damo, Ethiopia. Archaeologia, pg 43-46

Matthews, D., & Mordini, A. (1959). I.—The Monastery of Debra Damo, Ethiopia. Archaeologia, pg 53